“The chief cause of the capture of the division was the absence of the artillery from the line, the removal of which was ordered and carried out on the afternoon of May 11th.” (1)

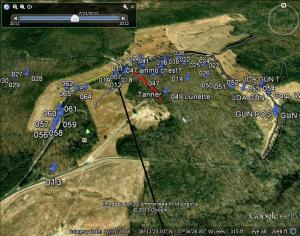

View from the apex of the salient.

Written years later this was Colonel Thomas H. Carter’s explanation for the disaster that befell Edward Johnson’s division within the Mule Shoe. He would continue “It was withdrawn the afternoon of May 11th by order of General Long, chief of artillery, second corps (Ewell’s), who was doubtless acting under orders, and who said the cavalry had reported the renewal of the flank movement toward Richmond by the enemy”.

So there we have it. Colonel Carter had been the second ranking officer in the corps artillery. As such he was assigned direct command of the artillery along the Mule Shoe line. If anyone outside the uppermost level of the Corps would know the facts it would have been him. He, like many Confederates writings on Spotsylvania in the period of from 1890 to 1910 agree on the cause for the disaster.

So was the Colonel, and the many others who shared his opinions about the withdrawal of the artillery that afternoon, correct? After all General Robert E. Lee, only days after the event called it “one of his blunders”. (2) Was the plan to actually to move or to prepare to move the army that night? And if was to move where to? To answer that question we don’t begin at nightfall on May 11th. Rather we begin at about 8:15 PM on May 10th.

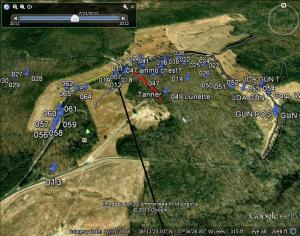

Google Earth of the Mule Shoe

Before we look at that however some boundaries need to be established. The first, and perhaps the most obvious, is that the armies would inevitably move from Spotsylvania Court House. Despite Grant’s well-known comments about fighting it out “on this line if it takes all summer”, the armies would inevitably move on. It was merely a question of which side moved first, in what direction and when. Secondly, this post is limited to the Second Corps units in the Mule Shoe. Both Alexander, commanding the First Corps artillery, and Walker the Third, were given orders to prepare for a move. Of course all the corps commanders would have received similar orders. But again we are only concerned with the Second Corps, and so we take up the story.

When Federal Colonel Emory Upton’s troops fell back to their start line the night of the 10th the Confederates were happy to see them go. Despite their entrenchments, the Federals had quickly punched a hole several hundred yards wide in the defenses as well as almost reaching the McCoull House, Edward Johnsons headquarters. While the Confederates had moved quickly, General Lee himself ordering replacement gunners for a battery forward, to seal the breach and drive the attackers out, they realized they had been lucky. Only the inability of the Federals to reinforce the success had prevented major damage.

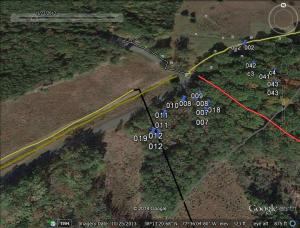

From in front of the works up the slope to Dole’s Salient.

The weakness of the line had been apparent to Gen. Robert E. Lee almost as soon as it had been created. On May 9, he had said that it was a miserably weak line, and did not see how it could be held. Now only a day later his fears about the weakness of the position had been validated. Even so the ease with which his defenses had been ruptured had to be a surprise. It was apparent that corrective action needed to be taken immediately, before the Federals could resume the attack. As soon as the battle ended he sent orders to Gen. Ewell directing specific actions correct weaknesses and to prepare for a renewed attack. So concerned was Gen. Lee that he personally visited the area of Doles Salient early the next day. Perhaps this was another indication of his mistrust not only of the line that Ewell held, but Ewell himself.

Throughout the following day the Confederates worked to prevent a repetition of Upton’s success. Not just shoveling more dirt onto the earthworks, but more effectively coordinating the defenses. This process would continue throughout the day and well into the night. At the same time there was a vigorous discussion among the leaders, at all levels, as to whether to hold or abandon the salient.

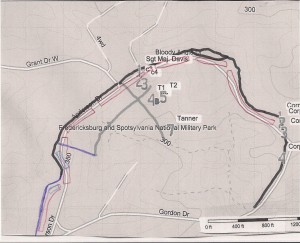

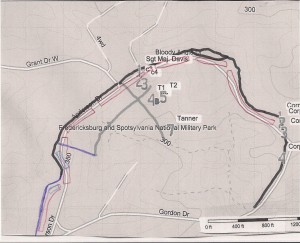

Topo of Mule Shoe showing lines and McCoull Lane

The portion of the line where Rodes’ and Johnson’s division joined was obviously a weak point. Why? Because of the proximity of the enemy and the dead ground out in front. This had been recognized, the morning after the troops had first occupied the position. Another major weakness was the total absence of artillery coverage, from either flank, of the ground in front of the works from the apex of Dole’s salient to the West Angle about 400 yards northward. Because of this Gen. Rodes had a second line built about 100 yards behind the main line. This second line ran perpendicularly from the main line near the right of Daniels Brigade. About one hundred yards back it turned sharply and ran across the field northward to approximately the extreme right of Doles Brigade. It appears that Johnson’s men had not taken similar precautions by extending the line behind the Stonewall Brigade. The line just ending midway across the field. During the afternoon of the 11th this was corrected, to some extent, by the Stonewall Brigade digging a line of rifle pits extending the line across the field and beyond the McCoull lane. Its ended approximately at the right flank of the Brigade. For some reason the line was not extended by either of the remaining brigades. Several theories exist as to why this was not done. One, and the most likely is that the right of Johnson’s line had not been attacked so it wasn’t considered necessary. . Another is that to do so while Carter’s guns were being withdrawn would have been difficult. Regardless for what ever reason it was not done. However the fact that there was no return or effort to tie the extended line into the main line along Johnson’s front seems to indicate that extending it was contemplated. (3) Finally, there was no need for it. It would be unnecessary, a waste of effort, if the troops were leaving.

Dole’s Brigade, which had taken major casualties the previous evening, definitely needed replacing by fresh troops.First, Pegram’s Brigade of Gordon’s division moved in about dawn on the 11th and occupied their trenches. But they were quickly replaced (4) by the Louisiana Brigade of Brigadier General Harry Hays of Johnson’s division. (5) Hayes men, along with the survivors of Brig. Gen. Leroy Stafford, had been occupying part of the line between the East and West Angles. That section of the line had been quiet, the only effort against it being Mott’s abortive attack the preceding afternoon. It is interesting that although Hayes commanding the combined Louisiana brigades, only his own brigade was ordered to move. While the reason for separating the two brigades again is unknown, perhaps it was because Hayes men were new to Johnson’s division. Regardless of the reason the remaining Louisianans under Col. Zebulon York (6) were ordered to spread out and cover the interval between the Stonewall and Jones Brigade. (7)

Col. Carter spent much of his day vigorously complaining to Gen. Ewell about the weakness of the line. He also may have shared his views with Gen. Lee when the General made his early morning visit to Doles Salient.. Colonel Carter was particularly incensed by the fact that the shape of the line prevented mutually supporting fires by his guns. Because the slope between Doles Salient and the West Angle concealed the Federals, his guns had initially been unable to take Upton’s men under fire. To do so he had been forced to move guns out to unprotected positions in front of the works. There, from positions nearly out in front of the West Angle, his men had been exposed with their backs to the enemy. (8) Fortunately the Federals had not been in position to make him pay for such a rash move. This fact, corresponded with Lee’s instructions to Ewell the previous evening indicating a flanking position should, if possible be found, highlighted the need for guns to be placed along the left of Johnson’s line. (9)

Given Gen. Lee’s instructions and the obvious shortcomings that Col. Carter had highlighted the two remaining batteries of Cutshaw’s battalion were brought forward. Early in the afternoon General Long personally selected positions for the guns and supervised the placement of the batteries. Carrington’s battery had one section in the main line just to the left of the West Angle, the other at ninety degrees to it along the McCoull Lane. Tanner’s battery (10) was still further to the left at the junction between Hays and the Stonewall Brigade. All of these guns were intended to enfilade the field up to “Doles Salient”.

Long’s choice of positions for those guns was not well thought of by those affected. Both Maj. Cutshaw and Brig. Gen. James Walker, of the Stonewall Brigade, strongly objected. They particularly wanted Tanner’s Battery of 3 inch rifles moved “further into the offset”. (11) Their objections were overruled, probably because it would reduce the ability to enfilade Doles Salient.The troops themselves did not like the position at all, seeing that it would be subject to a crossfire. Complaints to the battery officers were met with agreement as well as the usual response that orders must be obeyed. So work began on emplacements for the guns and equipment as well as protection for the men. This work would continue as long as possible into the night. Horses, who by this time of the war were almost as valuable as men, were taken to positions of safety behind the second line. (12)

So throughout the day the Confederates had been working to prevent a repetition of Uptons success. At the same time there was a vigorous discussion among the leaders as to whether to abandon the salient or continue to hold it. Gen. Lee had again expressed how objectionable he found the line. However his opinion was not shared by the division commanders. Both Generals Rodes and Johnson continued to insist that, with their breastworks made, they could hold their positions. (13)

Throughout the day reports had been coming in from scouts and the cavalry that there was movement behind the Federal lines. Among other things infantry was seen moving toward Todd’s Tavern, while a body of wagons were moving in the general direction of Fredericksburg. As a result by early afternoon the suspicion that the Federals may be preparing to move began to gain credence. As a precaution Gen. Lee gave orders to Gen. William N. Pendelton, army chief of artillery, to prepare for a movement by the army. Pendelton then sent written orders to each of the corps artillery commanders. They were instructed to have their batteries ready by nightfall to march with the infantry. (14)

Late in the afternoon there was another meeting of General Officers at the Harrison House. Although the reports of enemy movement conflicted they seemed to generally indicate a move toward Fredericksburg. As a result Gen. Lee began to feel that a movement by the Federals was imminent. Accordingly Gen. Lee ordered Gen. Ewell to withdraw Johnson’s division and its supporting artillery from its position. Evidently Rodes’ division was not included in this order. Interestingly enough Gen. Johnson was not present at the time the decision was made, he was reconnoitering along his picket line. His absence would make itself felt latter. Gen. Ewell spoke up and suggested that the men would be more comfortable in the shelter of the trenches than if they were out in the open. Gen. Lee agreed and let the infantry stay in their positions. The supporting artillery however would be withdrawn as ordered and the horses allowed to graze. (15)

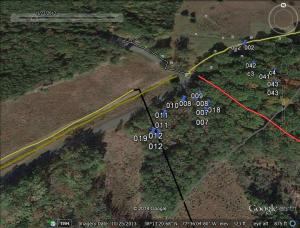

Gen. Long therefore ordered Col. Carter to withdraw the battalions of Nelson and Page. which occupied positions on both sides of the East Angle. These guns would go out by the farm lane which led across the run below the McCoul House and back past the Harrison House. Near the Brock Road the routes of the two battalions would separate. Nelson would veer left and continue on to his camp behind the Courthouse, while Page would turn to the right and cross the Brock Road onto the Trigg Farm. Because of the difficulty of negotiating the stream it would be best to move the guns out before dark. (16)

As these units were beginning their withdrawal Gen. Johnson returned from his reconnaissance. Not yet knowing of the decision to withdraw the artillery he demanded to know why the guns were being withdrawn, leaving his men unsupported. (17) Col. Carter, perhaps not wanting to get into a confrontation with the General could only tell him that while he and his men would prefer to stay they had their orders, which were to withdraw.

At some point during the withdrawal of the guns, Col. Carter met Maj. Robert Hardaway, several of whose batteries were supporting Rodes division to Johnson’s left. The Colonel informed him that all the guns were being pulled out at dark. This was a surprise to Major Hardaway, but being an experienced commander, he passed this news not only down to his battery commanders but also to Brig. Gen. Stephen Ramseur, the closest infantry brigade commander as well. (18)

For some reason Maj. Hardaway had some doubts about Colonel Carter’s news. Perhaps it was simply that while the Colonel outranked him, he was not his immediate commander. Gen. Long, had since the death of J. Thompson Brown in the Wilderness, directly controlled Brown’s Division of artillery of which Hardaway was a part. (19) Since Gen. Long had not sent him orders to move the Major went in search of the General. As it turned out he found both Generals Lee and Long at the Harrison House. When asked one of the Generals (20) responded that Colonel Carter was mistaken. It was not intended that Hardaway’s guns should move from their positions until the infantry did. His curiosity satisfied, Hardaway once again sent word to the various commanders, this time that they were not moving. Hardaway then proceeded on to his battalion’s camp behind the Courthouse.

While in the Salient Gen. Long had ordered Maj. Cutshaw to have his horses brought up to the guns from their positions behind the second line. Doing so would prevent any delay or confusion when the infantry moved. The previous afternoon, only a couple of hundred yards to the right, the hasty withdrawal of Nelson’s battalion had greatly inconvenienced the infantry. The troops to the right could barely get past in their attempt to move over and confront Upton. It was impressed on Cutshaw however that he was not to begin to move before the infantry of Johnson’s division did. Meanwhile the men of the newly arrived batteries of Carrington and Tanner continued to work on the emplacements for the guns.

Having had the horses brought forward Major Cutshaw went to Gen. Johnson in an effort to find out when the movement of the infantry could be expected. General Johnson could not answer the question however. He told the Major that he was unsure as to what his orders would be. Finding that there was no immediate need the Major then asked for permission to send his horses and sick men back to the battalion’s camp. After considering the request Johnson gave his permission for them to go. Certainly one of the things that the two men had to consider was that, until the horses were returned the guns would be immobile. Therefore there should have been an agreed time for the return of the horses to prevent any delay with moving the guns..

Each of the battery commanders of Cutshaw’s battalion were ordered to send the horses as well as sick men back to camp. There was some discussion in at least Carrington’s battery as to who would go back. It would normally be the Sergeant Major’s job to supervise the task. In this case Sergeant Hunter, who commanded one of the guns, was expected to receive his commission momentarily. Therefore he was tasked with taking the guns out while the Sergeant Major took over his gun. (21) This itself was an indication that no action was expected. Before he left for camp the Major was overheard, by Sergeant Major Davis telling Captain Carrington that he could expect orders in the early morning to move. (22) The route of march likely would be “out the road which ran thru the works” i. e. the McCoull Lane. Cutshaw then went on to the battalion camp on the Trigg Farm on the southern side of the Brock Road. Pages battalion also camped on this farm that night. It wasn’t long before the battalion executive officer, Major Stribling, joined him. He was able to report that when he left the front “all was well”.

When all the movements were finished the Salient once again grew quiet. Men put the last touches on the fortifications, ate, and generally settled in for another wet evening in the field. Commanders generally went to their headquarters to perform the administrative duties required before relaxing for the evening. And where did these men spend the evening?

General Lee returned to his headquarters camp. General Ewell is generally assumed to have spent the evening at or near the Harrison House. However, the topographer Maj. Jed Hotchkiss, whose wagons had been brought up to the intersection near the Frazier House during the day, gives a different version. He wrote in his diary that “the General” joined them for a period that evening. (23) Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson was at the McCoull House. He would stay either there or on the line the entire night. We do not know the exact whereabouts of Generals Robert Rodes and John Gordon but must assume they were with their commands.

The various artillery commanders were scattered about, at their respective headquarters that night. . General A. L. Long was at his camp, most likely on or near the grounds of the Harrison House. Colonel Thomas Carter was nearby but likely on the grounds of the Trigg Farm. (24) All of the battalion commanders were at their respective camps that night. Majors Carter Braxton, Robert Hardaway and William Nelson were with their battalions behind the Courthouse. Majors Wilfred Cutshaw and R.C. M. Page were their respective camps on the Trigg Farm. No artillery commanders other than the individual battery commanders were at the front that evening. On Johnson’s line Capt. Carrington was the ranking officer of the two batteries near the West Angle.

So was the Second Corps going to move that night? If not that night when? And if they were going to move where were they going to move to?

In my opinion the evidence is pretty conclusive that the anticipation was that they would be moving in the near future. There is no doubt though that they weren’t going to move during the night of the 11th. As to where they were going to move that depended on the Federals. Although the consensus seemed to be toward the right, perhaps toward Fredericksburg. So lets examine each of the questions separately.

It’s very obvious, from the accounts of both Campbell Brown and Thomas Carter, that Gen. Lee wanted to evacuate at least that part of the salient held by Johnson’s division. While Gordon’s division had built a line in front of the Harrison House when they arrived it had proven unsatisfactory. Enfilading artillery fire had forced it to be evacuated almost immediately. As a result work had been begun as early as the 9th on another line through the woods to the rear of the Harrison House. That line, which we call the “Final Line” today, would eliminate the salient altogether. When General Lee had floated that idea however he had met resistance from all the infantry commanders other than perhaps Gordon. Certainly the two division commanders, Robert Rodes and Edward Johnson, despite Upton’s success, insisted that they could hold their existing lines. However while this debate went on, reports of Federal movement continued to come in. These reports seemed to indicate that Grant was making the preliminary moves necessary before moving his army away from Spotsylvania. Therefore Gen. Lee, after consulting with his subordinates decided to abandon the salient. Doing so, which he had wanted to for several days, would position him to exercise one of several options. He could take up the new line under construction across the base of the salient. This line was shorter, more defensible while still allowing him to control the road network. In addition by moving Johnson back he would be much closer to either the Brock or Fredericksburg Roads, These would be the primary routes regardless of which way the army moved. So regardless of the direction of Grant’s movement he would be able to more quickly react. Therefore he ordered both the infantry as well as the artillery on Johnson’s divisional front to be withdrawn. Regardless of the reason for evacuating the salient, the artillery, or at least the bulk of it, must move first. Otherwise it would hinder the movement of the infantry,or be vulnerable without infantry support. Perhaps this is why he acquiesced to Ewell’s suggestion that the men would be more comfortable in the trenches. However as long as the infantry stayed in position they needed artillery support. Since Rodes had been fighting for intermittently for three days his need for support was obvious. Johnson however had not been attacked at all. Therefore there he had no real need for support. So the supporting guns could be withdrawn with little risk. The artillery that remained on his line, actually supporting Rodes, would have easy access to the roads to either withdraw or advance.

As to when the move was planned the evidence seems indisputable that they had no intention of moving that night. It seems most likely that they expected to move sometime the next morning. Certainly General Lee had instructed General Long to draw out the artillery along the front of Johnson’s division. It is notable that the senior officers didn’t mention anything about the withdrawal route being difficult to negotiate. That is only mentioned by either junior officers or those who were not in the artillery. As we discussed in the previous post Gen. Long used the orders to withdraw all but those units which would march with the infantry, i.e. Cutshaw’s and Hardaway’s battalions. Yet the infantry were allowed to stay in the trenches on Ewell’s suggestion, certainly until morning.. Therefore the horses of Cutshaw were allowed to be returned to camp for grazing. The only reason a commander as experienced as General Johnson would have allowed this was if there was no need for them. Obviously these horses would have to be returned before Cutshaw’s guns could move. Presumably Cutshaw and General Johnson had made some agreement as to what time the horses needed to be back. If so it could not have been at earliest dawn. We know that they were not back when Hancock’s attack was stopped below the re entrant line. Captain Garber had to, by Robert Rodes order, have his guns manually withdrawn and re oriented to fire on the advancing Federals. (25) Also neither Hardaway nor Cutshaw saw fit to stay at the line that night. As a result neither one was there when the battle opened. Hardaway was wounded by shellfire on his way back. Cutshaw didn’t join Garber until the struggle to hold the reentrant line. (26) Again the actions of the artillery show pretty conclusively that the move would not be made that night.

People have to make decisions based on the information they have. The decision often times is simply the lesser of two evils. And sometimes it involves taking a calculated risk. That is what happened I believe on May 11th around the Harrison House. Experienced leaders made a decision that didn’t turn out the way they thought it would. The result is history.

In closing I would like to ask …… Is the real issue here the leadership style of Robert E. Lee? The fact that he gave too much leeway to his subordinates? That he chose not to follow his instincts and order his subordinates to take the difficult course? That he should have overruled Ewell and his division commanders and abandoned the line? Perhaps history would have taken a different course if he had.

I welcome any comments or discussion that people may have. Trying to interpret the intentions of people is difficult at best, and surely there is room for debate.

(1) SHSP Vol. 21, pages 239-242. “Colonel Thomas H. Carter’s letter” both this comment and the one in the next paragraph were in this same article published in 1893. In a letter to John W. Daniel in 1904, declining to write the history of the Virginia Artillery of the Army of Northern Virginia he merely attributes the loss of the salient to the absence of the artillery. This is a simplified version of what he wrote to his wife immediately after the event.

(2) Quoting from a private letter from Thomas Carter to his wife May 24, 1864.

(3) A Federal sketch map does show a second line behind Dole’s salient. However Lt. Doyle of the 33rd Virginia, Stonewall Brigade referred to a line of rifle pits being built on the 11th. A detailed examination of the ground shows what appears to be a unit boundary along the second line. There is a slight change of direction as well as a difference in the construction.

(4) some of the Virginians thought they were only in the line for about one half hour.

(5) Hays was wounded, whether by shellfire or a sniper’s bullet is not clear, and replaced by his senior regimental commander Col. William Monaghan of the 6th Louisiana. Accounts vary as to whether Hayes was wounded on the 9th or the 10th. There are conflicting accounts as to who was actually in command of the combined Louisiana brigades after Hayes was wounded.

(6) when Leroy Stafford was killed in the Wilderness the next in command was Col. Zebulon York of the 14th Louisiana. However, as part of the reorganization done so that John B. Gordon would be senior Brigadier, thus division commander in Jubal Early’s absence both Louisiana Brigades were consolidated under Harry Hays and placed in Johnson’s Division.

(7) Moving Hays men only is an interesting decision. The number of his men alone, roughly 800, didn’t equal Doles losses much less his total strength prior to Upton’s attack. That would have required that both brigades of Louisianians be moved. So if the Louisianians occupied Doles entire section of the line it was actually weaker, not stronger. Also was it only Stafford’s Brigade that spread out, or did Jone’s and the Stonewall also? Regardless this move lengthened and weakened Johnson’s line, both at the point that Hancock would strike the next day and where Upton had struck as well. Yet perhaps it was simply that Ewell did specifically order that Hayes brigade be given the job. BTW: Hayes was wounded and not on the field May 12. There are conflicting accounts of whether he was wounded on the 9th or the 10th.

(8) To take a position outside of the works with their backs to the enemy showed both ingenuity as well as desperation. Mott’s men were still in the woods beyond the Landrum House, while Burnside corps was astride the Fredericksburg road.

(9) Lee had sent instructions to Ewell at 8:15 pm pointedly giving him instructions as to measures he wanted taken due to Rodes being so quickly overwhelmed. Note also that the timing of the note indicates that it was only two hours after Upton had begun his attack.

(10) The battery was actually commanded by the senior Lieutenant, 1st Lieutenant Benjamin C. Maxwell. Capt. Tanner had been so severely wounded at Bristoe Station that he had been left behind and captured by the Federals. Maxwell was an ancestor of this writer who had enlisted as a private, been elected sergeant and risen thru the ranks due to the misfortunes of others. At the time of Tanner’s wounding he had been the senior Lieutenant, thus assuming command.

(11) Major Cutshaw also wrote that Tanner’s battery was in a “slight offset” just to Rodes left in a “slight offset” He obviously meant to Rodes right rather than his left. His use of the word “offset” I take to mean salient or bend in the line. Thus a small bend just to Rodes right. As to the objections of Cutshaw and Walker it seems apparent that both men wanted the battery closer to the right of the Stonewall Brigade. Moving them more in that direction would come up again during the evening.

(12) “Second line” would most likely be what we today call “Gordon’s” line. Today the line behind the main line from the re-entrant to the right of the McCoul lane is referred to as the second line. However the participants themselves did not.

(13) Col. Thomas Carter letter to his wife May 15. Another version of this story says that Gen. Ewell convinced Gen. Lee that the troops would be more sheltered from the rain in the positions in the salient. I think that both are true simply referring to separate events. That seems apparent because of Carter’s inclusion of General Johnson, and Johnson’s not knowing the guns were to be withdrawn. However the question is where did Lee think they were going to go? Unless they were actually going to move to put them in the open until breastworks could be built would appear to be risky.

(14) Surely the infantry corps commanders were given similar orders by Lee himself. However none of them mention it in their later writing. Ewell did say that Gen. Lee had information that the Federals were preparing to move. Nor does Jed Hotchkiss who wrote in his diary that the enemy appeared to be moving to the left.

(15) Campbell Brown Papers, Tennessee State Library

(16) Today you can see that on the south side of the current park road this stream, Meadow Run, becomes a swamp. On the other side of the road, back almost as far as the spring, it is a tranquil small stream. At some places, particularly near the west McCoull Lane, capable of being jumped by an average adult male. However below the house and to its right the banks are steep and unfriendly. As you near the marsh the banks flatten and it becomes easier to cross.That said the spring was capped years ago which may affect these observations. That said the pioneers could have easily built bridges across the stream at virtually any point. But since the accounts talk about the marshy bottom it would clearly seem to indicate a point near, but to the left of the current park road.

(17) Gen. Johnson would say later that during his reconnaissance he had seen no evidence of Federal activity in his front.

(18) Hardaway in his article published in a Richmond newspaper would say he notified Ramseur. Ramseur was in command of the infantry brigade which Hardaway’s guns were in immediate support of.

(19During the winter Gen. Long had divided the artillery into two divisions. These were commanded by Colonels Brown and Carter. In the orders creating the divisions he had specified that in the event of something happening to one of them, the Corps artillery commander would take command of his division. To confuse matters even more however in some places Carter is referred to as commanding the artillery in the salient.

(20) Maj. Hardaway identified the Generals as Gen’ls L. and L.” This can only be Lee and Long. He says only that Gen’l L. clarified his orders. It really makes no difference which. As the two were together they essentially spoke with one voice.

(21) Sergeant Major Wilbur Fiske Davis said that they were expecting battle shortly and that he asked for the change. More likely it was to give the young sergeant a task of larger responsibility with an easy assignment. In battle the Sergeant Major would be responsible for ammo supply, management of the horses, etc. Duties much more important to the functioning of the battery than commanding a single gun. It seems unlikely then that they were expecting anything important to happen during the night.

(22) This, if true means that both Johnson and Cutshaw were not anticipating a move that night.

(23) Fraziers is over a mile from the Harrison House. When the General arrived and departed is not mentioned in the Hotchkiss Diary. Diary of Maj. Jed Hotchkiss, page 203-204 His actual reference is to “the General”. This is the term he had earlier used for Jackson and seemed to transfer to Ewell after Jackson’s demise. As confirmation he mentions every day for the next several days that “the General” stayed at the front.

(24) I must admit both of these are educated guesses. Both Cutshaw’s and Page’s camps were on the Trigg Farm. Since Colonel Carter physically met with Maj. Page before he led his battalion to the front the next morning. Also Carter had until recently commanded Pages battalion. Therefore it would be likely that he camped with those units as well.

Carter just said he was “back with General Long” or otherwise “near General Long”. The Corps commander would have wanted his artillery commander nearby therefore the Harrison House grounds seems likely.

(25) It is interesting to note the difference in the way the division commanders acted toward the artillery. Johnson had given Maj. Cutshaw permission to withdraw the artillery. Yet during the night, when Capt. Carrington suggested moving either his own or Tanners battery to a more favorable position, Johnson said he would have the horses sent for. Rodes on the other hand ordered Garber, whose horses had not been returned, to move his guns to the rear by hand. Admittedly the battle was raging when Rodes gave his order.

(26) One of the unanswered questions is when did Cutshaw start his horses and drivers back to the front. We would expect that Carter would have informed Cutshaw when he had Pages men alerted. Gen. Long’s comment about Page’s return. That they left so swiftly that nobody noticed it. Who would have been there other than Cutshaw’s men? Cutshaw naturally went to Garber’s position. The whereabouts of the rest of his men is uncertain.